Frank O. Gehry Architetture residuali

by

Antonino Saggio

Published in Italian by

Testo&Immagine Torino 1997

English Translation of the first

paragraphs of the book

Courtesy of Testo&Immagine

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE

Frank O. Gehry Architetture residuali

by

Antonino Saggio

Published in Italian by

Testo&Immagine Torino 1997

English Translation of the first

paragraphs of the book

Courtesy of Testo&Immagine

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE

Frank Owen Gehry opened an efficient architectural office in 1962, but sixteen years later, almost overnight, he subverted the canons of his everyday professionalism for a new and audacious experimentation. This was the opening of an intense period of research, reflected in his one man show in 1986 which launched him into the international limelight. Together with receiving the most coveted recognitions any architect could hope for, dozens of constructions followed on both sides of the Atlantic: the American Center in Paris, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the Disney Auditorium in Los Angeles are all works and symbols of this period at the end of the century.

Of all his many traveling companions, it is Gehry who brings together sculptural power and the sense of space, hollow and jagged, within an esthetic which examines the swirling evolution of society. The projects were constructed in an incessant experimentation with very different materials. They come into contact with their physical locations in a bold and provocative manner. They present an explosive expressiveness, fluid and dynamic. And finally, they also deal with those powers financing, promoting and building the works. The many pragmatic aspects of our way of doing things move within the synthesis of architecture as art and not vice versa.

The work of a genius breaks through the conventional, known limits of his own discipline in order to redefine roles, to bring meaning back into the present. Architecture creates the patterns (the forms, the recurring containers) of life and living. The architecture of Gehry helps us live out the present with intelligence, depth, opportunity, stimulation, love and real democracy instead of stupidity and unhappiness. In remembering the happiness and hope of all architecture, his work is useful. In rekindling, in far off and backward countries, an aggressive commitment to design, Gehry becomes indispensable.

1. Year 49, Level Zero

1.1 Reshuffling the Pieces of the Pattern

In 1859, in the countryside of Kent, a Red House was created whose individual parts were freely mounted and autonomous; no more classical columns, no longer a uniformity of view points or the reassuring certainty of closed volumes, but instead an episodic quality of forms and materials opening themselves up to the embrace of nature. In 1913, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space was cast; the muscles of a walking man curved and deformed in tension to penetrate the air. On a fall morning in 1935, a house was designed which incorporated the movement of a waterfall. The planes were disjointed, moving in a helix on three Cartesian axes like water pushing the paddles of a mill; the stairs and fireplace rearing up above dizzying leaps of terraces; stone, iron, glass and reinforced concrete wedged together into a new landscape. At 49 years old, an American architect in Rome for a year discovered a new way of seeing architecture and its deepest motives. He set the customs of his academic training back to zero, along with the rigidity of his earlier functionalism. He left the archaic in order to affirm the most profound aspects of building: structure and form, function and light became intimately associated.

In 1960, in a small studio in New York, the La Strada show opened. With irreverent curiosity, the focus of art now turned toward the ugly objects of daily life. Six years later, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture was published. Advertising, mass production and consumption, kitsch and popular taste penetrated even into the architectural debate. At the same time, construction was begun on Kresge College in a small California university town. A new awareness arose of open space "encircled" by buildings. In 1969, a year after the pacifist revolts at Berkeley and Columbia, a theater in Oklahoma City was created with independent parts launched into space, connected by tubes and conduits to a noisy machine. From the music, the sounds of the world were echoed in the construction. In 1978, a forty-nine year old architect built an extension to his own home. It was a new, explosive beginning for the architecture of tomorrow.

We are dealing with a work which emerges unexpectedly. The architect who designed it had created several stimulating works, but the thread running through his remarkable production had been marked with serious professionalism; knowledgeable, responsible and as "socially correct" as it was far away from the art that had interested him as a very young man.

Frank Owen Gehry was born in Toronto on the 28th of February, 1929. His Hebrew name was Ephraim and his scornful nickname, Fish. Having left Canada immediately after the war, he moved to Los Angeles where he lived with his family, not in a little house in the green suburbs but in the dense and dangerous city center.

In California, he changed his name from Goldberg to Gehry and got to know a bit of the glittering Hollywood movie scene. But in 1952, at the age of twenty-three, he was still "a duck out of water". It was Anita Snyder, a secretary with her feet on the ground and a modest salary supporting her, who married him and helped him find a direction. And so he made it to the University of Southern California. After having begun but then abandoned his art studies, he finally graduated in architecture in 1954. A little while later, in the army in Georgia, he designed his "Wright-esqe fantasies" and built small works with those simple materials which he had sold and stored as a boy in the hardware store of his grandfather, a socialist Jew who gave him his second name of Owen. He had already met Victor Gruen, who had arrived in Los Angeles (following in the footsteps of the more gifted Schindler and Neutra) from Vienna just before the Anschluss. Gruen had a solid and reputable office which would go on to create hundreds of works. He advised the young man, having finished his military service, to throw himself into the true calling of the fifties architect: urban planning.

Gehry, twenty-seven years old and the father of two children, then enrolled in the Harvard School of City Planning. Despite receiving the prestigious degree, Boston did not work for him and in 1958 he returned to Gruen. This job would continue for two years. But in order to get out of a stalled situation and the lack of career prospects, he moved to Paris with his family. He worked for a year for the architect André Rémondet and also traveled some. He got to know the two most recent works of Le Corbusier, La Tourette and above all Ronchamp, which, along with the French and German Romanesque churches (as sculptural as they were free and non-perspective) would be stored in his personal aspirations. Then, on returning to Los Angeles, the great leap. In 1962, he opened an office under his own name.

Production was almost immediately impressive and of good quality. In the beginning, there were buildings in a admittedly "Wrightian" vein, but ones which also revealed a knowledge of the Greene brothers and Schindler. He drew up zoning plans and designed stores, housing projects, offices and open air theaters and built almost thirty works. His oeuvre was well-accepted by the American professional class, so much so that in 1974 he became a Fellow of the AIA. Along with projects commissioned publicly or by businesses, he had some small opportunities to experiment in several decorating jobs and two house-studios for artists: the Danziger (a minimal composition of volumes closed-off to the city) and the Davis (a research into the dynamic perception connected to the trapezium; an irregular four-sided figure).

At the beginning of the Sixties, he built easy chairs out of corrugated cardboard. A work which, at that time, could have only been considered within the experimental freedom of a radical design. He also taught a little at SCI-ARC (the Southern California Institute of Architecture), a place which would become a driving force in the dispersion of the Los Angeles city-region. But his academic role was secondary and temporary and his qualities as a communicator were less than charming.

From the personal point of view, despite the stability of the studio, which included around twenty collaborators, his "world was not working very well". He was helped by the psychologist of the artists, Milton Wexler, a personality who fascinated Gehry and may have helped him understand how to challenge life on a higher plane. In 1976, ten years after his separation from Anita, he married Bertha Isabel Aguilera, and in 1978 construction was completed on the home they had bought for their new life.

The significance of this house goes back more than a century to the Red House that the young Webb constructed for William Morris. That was the beginning of an artistic thread which, through the utilization of craftsmanship and relationships with industry, would lead to Bauhaus functionalism. In this house, in a neighborhood of suburban one family homes, the divisions would be challenged - for the first time from their very foundations - between the courtly and the popular, between the sophisticated and everyday, between elite "high" culture and mass "low" culture.

From the point of view of the creator, this was a re-foundation; a "level zero", comparable in force and intensity to that felt thirty years before by Louis Kahn in Rome. Both of them, on the verge of fifty, decided, even if on very different coordinates, to separate themselves immediately from architecture as a craft in order to wed themselves to architecture as art, as a courageous search, with no holding back. At the crossroads of this regenerating journey, Gehry absorbed the equation: new house = new architecture.

But then again, responding to life and its turning-points is the true work of an artist.

Technically this was an addition. A

small house, the image of the well-mannered taste of the New World, was

bought in the great city-region. His wife liked it and it was entrusted

to the hands of her husband, the designer, in order to extend its functions,

which also had to consider the dynamic needs of the couple’s two very young

children.

Gehry loved and hated the image of this house. He "understood" it within the confines of the lower middle-class tastes of his neighbors in Santa Monica and yet he rejected it at the same time. The choice of floor plan already revealed his mixed emotions. He did not demolish the construction, perhaps substituting it with the blank architecture of the New York Five. He did not gut it, modifying the interiors and keeping the façade intact. He did not construct an independent addition which might echo, perhaps with a biting interpretation, historicist and popular components. He wrapped the new home, loaded at one and the same time with standardized collective values and the weight of its own diversity, in a "U-shaped" structure.

One side of the cube remained intact, even from the functional point of view. But innovation broke out on the other three. A new entrance screen was defined on the ground floor. The horizontal section of the "U" (which opened onto the corner of a connecting street) was occupied by the kitchen, with two areas of different functions for the dining room. In the rear garden, the form was completed with a portico-gallery.

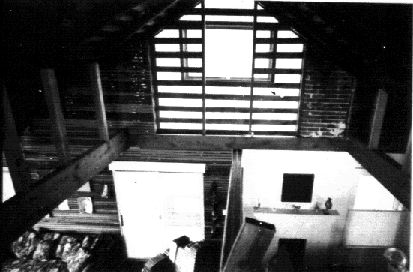

The spatial quality of the house was completely deformed. Beyond the staircase separating the bedrooms, a swirling space was defined, centered on the living room. Entryway, dining room, kitchen, breakfast area and studio were all visible from the center. A series of superimposed planes opened up in consecutive screens from the interior shadows to the light. On the upper floor, the addition surrounds the double environment of the master bedroom with communicating walkways and terraces (onto which opened irregular prisms bringing in angular light from below). The demolition of the counter ceiling created an intense three-dimensional quality in the interior of the room. A free, non-conformist life-style emerged, half industrial loft and half set-design, filled with courage and love.

He encircled the little pavilion-style house with tin panels, plywood sheets, metallic netting and bricks painted with an electric blue-green. The windows are just slightly recessed into the sheet metal. The doors exist within sheets of plywood. The skylights are made of un-treated wood which holds up the glass in planes not right-angled to one another. The asphalt of the street penetrates all the way onto the kitchen floor. The banisters of the walkways are transformed into cages, rising-up crookedly like antennae, made of the same poor chicken-wire mesh; (also to keep his children from playing Superman off them.) The surrounding space is invaded by a play of obliques, of forms free from one another, of rotations and spirals, down to the introduction of the helical steps on the entrance lawn.

He justified the house by pointing out to his neighbors their sheet metal trailers, the boats of molded plastic, the chain link wire mesh of the fences, the untreated wood of the garages, the gaudy colors of the metal accessories they put in their back yards. But from the idiosyncrasies of these yards, this world was dragged to the forefront of a new sensation. The shock was very violent. The Gehry house pierced the curtains of the neighbors across the road, penetrating into their living room. Seen through the eyes of a neighbor, the addition was an artificial limb (abominable and mechanical) added to the body of the old doll inherited from grandmother. But to a more trained eye, it recalled the scandalous violence of all art at its birth: Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Manet, Picasso.

Gehry knew that the negativity of art (saying "no" to what is going on) was necessary in order to affirm a different "way of knowing".

It looked like the work of an habitué of avant-garde exhibits, an architect-artist who closely followed the progress of the latest experiments, or of someone who listened to twelve-tone music or the most hybrid sounds of new jazz or rock music. In other words, it "seemed" like the work of an anti-establishment architect of protest; one who searched in the "poor", in the lack of adornment and maybe in pre- and post-‘68 counter-culture movements, for some gesture that would slap respectability in the face. In fact, he did frequent the artistic scene (which at the time was even more liberal and anti-conformist in California than anywhere else). He was attracted by the materiality present around him, especially that casual and disordered one of the suburbs. He spoke to the producers of corrugated metal, wire mesh, cardboard and plywood in order to discover new potentialities in these materials. He was attracted to creating the unfinished, rebellious, oblique and even rickety.

But even though present for years, these ambitions of his had been substantially repressed in architecture up to this point. The real breakthrough came with his own house, which takes on not only a redeeming significance but also becomes the concrete proof of a different possibility..

Index

in red what is avalaible in this

english Translation

Istruzioni per l’uso

1. Anni 49, Grado zero

1.1 Tessere da rimescolare

1.2 Gehry senz’acqua

1.3 Joy story

1.4 Fioriture metalliche

1.5 Primitivo di un nuovo sentire

2. Vuotometrico e nuove icone

2.1. Ballon frame all’arsenale.

2.2 Gerarchia di figure spaziali

2.3 Con Borromini

3. Operazioni

3.1 La fenditura esplosa

3.2 L’edificio in stadi

3.3. L’edificio manifesto

3.4 Danze d’architettura

4. Traiettorie nello Spazio

4.1 Miracolo a Minneapolis

4.2 L’atmosfera che circonda le cose

4.3 Ricostruzione gehryiana dell’universo

4.4 Traiettorie e collisioni

4.5 Nuove cattedrali

5. Liquidare

5.1. Tecniche

5.2 Scuola Gehry?

5.3. Un nuovo inizio

Per approfondire